(Image from @svenshaw)

Stefani Langehennig and Ben Worthy

9 December 2019

MPs are now under the closest scrutiny, as their records, behaviour and actions are ruthlessly combed over. So what can we find out and what can it really tell us? Our new project looks at monitory democracy, the idea that a whole host of formal, informal and somewhere in-between bodies are scrutinising those in power, looking in particular at Westminster.

Take the example of Boris Johnson as an MP. In some ways, he’s a rather bad example, because as prime minister, there’s more scrutiny going on than your average MP, especially now. You can find out what gifts are given to PMs (this is May’s rather than Johnson’s, which are yet to be published) and who they’ve been meeting. But he’s also interesting because he seems somewhat averse to scrutiny, and is a good example of what different data can and can’t tell us about our elected politicians.

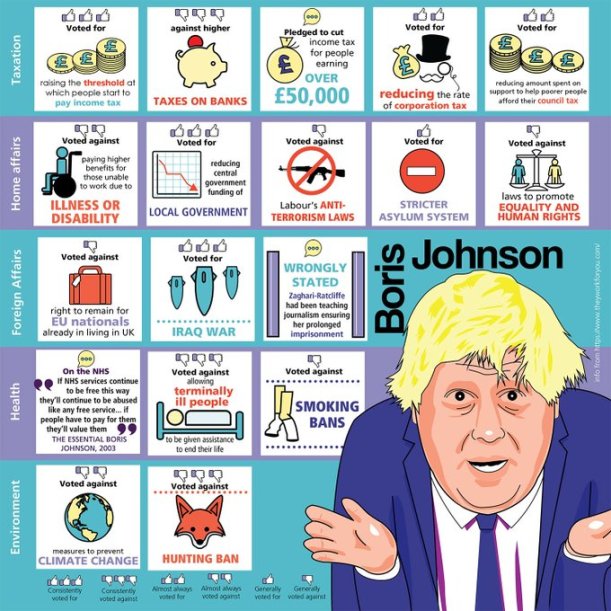

One obvious starting point for monitoring is Boris Johnson’s voting record. For MPs, it’s often used as a short-cut to get a sense of where they stand, their integrity, their honesty and what they may do in the future-see this comparison of Swinson, Corbyn and Johnson’s LGBT voting record. We can see where Johnson stood on some controversial issues: He voted strongly in support of Iraq war, and the hunting ban. He voted twice against May’s deal but backed it the third time around. Here’s a great example measuring up Johnson’s claim to have been against austerity to his record:

Since returning as an MP in 2015, Johnson has consistently voted in support of austerity policies…He almost always voted for a reduction in spending on welfare benefits [and] consistently voted for reducing central government funding for local authorities.

But this data doesn’t tell us the whole story. Johnson only backed May’s deal because he reached the ‘sad conclusion’ that he had to. He supported the Iraq War but later supported investigations into it, which points to a change of mind (or at least the appearance of one). He was also, especially in his early years, a notorious absentee from many votes.

A browse of an MPs’ registers of interests is illuminating. For Johnson, it shows us that actually, like Churchill, he has used his pen and earned from it. You can also see political donations and his links to the pro-Brexit JCB, who contributed to his campaign and gave him helicopter flights. We can’t again know everything, especially given Committee on Standards chastised Johnson for his ‘over-casual attitude towards obeying the rules of the House’ for which he seemed to profusely apologise. Rumours abound of money from elsewhere, especially Russia.

The more determined monitors could use FOI, one monitory tool that can open up the sometimes grey area between public and private life. It famously helped open up MPs’ expenses. It came bounding into the General Election campaign when Corbyn held up documents, obtained under the Act, seemingly showing the NHS was for sale.

For Johnson, the Act has been used retrospectively to look into his past, with the Guardian checking his Mayoral diary for meetings with Jennifer Arcuri or who he lobbied over his famous Garden Bridge. There’s now a whole range of monitory bodies and investigations weighing in on his time as Mayor, some of which have been put on hold while the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) investigates itself.

Such data can reveal and hide what our elected representatives are doing, as Marie Le Conte points out here. It doesn’t tell us about some of the hidden influences on members, such as the huge over-bearing influence of party or the pull of sheer ambition. The data can be read in various ways: is Johnson’s voting record journey from centrist liberal to hard core-Brexit or is it the work of a zig-zagging opportunist? Does his register tell us that is he a successful entrepreneur and writer or someone who just breaks rules?

But data offers us the opportunity to more comprehensively track the activities of our lawmakers and the public’s reaction to these actions. For example, tracking the behaviour of backbenchers uncovers strategies that significantly impact the outcomes of Brexit deals, while social media data suggests that an increasingly polarised public has fuelled politically-defining moments such as Brexit, as well as the rise of Boris Johnson.

These data provide the public the opportunity to hold lawmakers accountable in ways not available before. But whether it does make a difference may very much depend on who is watching.

Our preliminary analysis of followers of @TheyWorkForYou offers a glimpse of the types of followers who track it. Of the more than 4,000 followers, approximately 79 percent are everyday citizens that are engaged in monitoring their lawmakers. While much smaller, more than 4 percent of MPs serving in Westminster engage in monitoring their own legislative actions, while around 7 percent of are academics, charities, and other non-political public organisations. Are the public swapping memes of their MPs’ voting records as they prepare to vote? Are academics crunching voting numbers? And why, exactly, are MPs monitoring themselves?

Stefani Langehennig and Ben Worthy are working on a Leverhulme Trust funded project ‘Who is watching Parliament?’ looking at how new data sources and web platforms have made it easier to monitor Parliament and its members. Image credit: see http://www.svenshaw.com/